You have a meeting in 1min and you need to operate some foreign vidcon equipment. Choose wisely.

You have a meeting in 1min and you need to operate some foreign vidcon equipment. Choose wisely.

I survived my first day at the new job. Let’s see if I can do another one!

French gamers! Le financement participatif pour la VF de la nouvelle edition de Runequest est en cours: https://www.gameontabletop.com

Well that’s it, my last day at EA on the Frostbite team. I’m saying goodbye to this awesome giant screen. And also to my nice colleagues. But mostly the screen 😅

Of course I caught a cold on the day BC broke a 17 year old temperature high record 😓

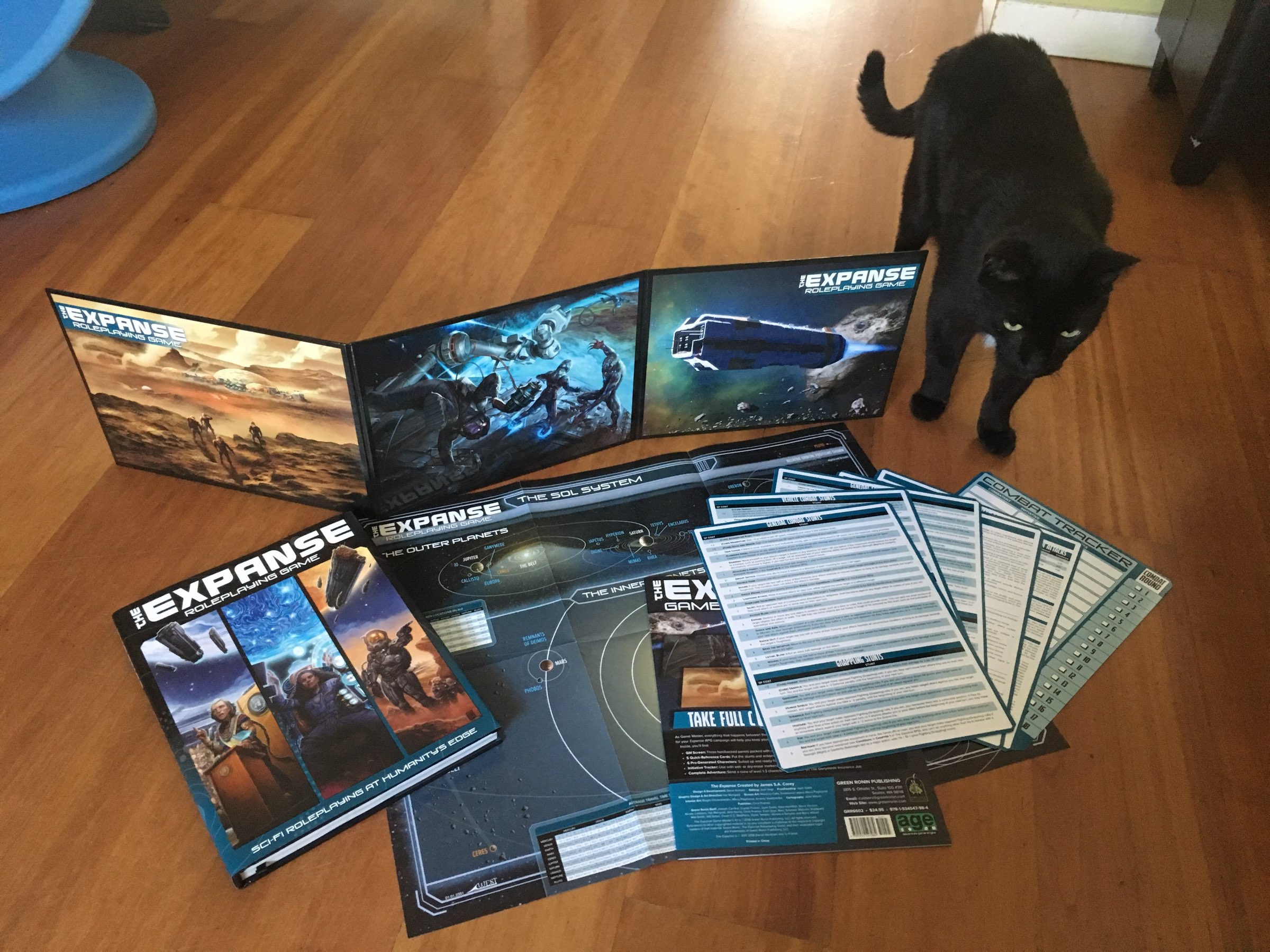

Lestat surveys this nice bundle of The Expanse RPG that I backed on Kickstarter a while ago. He seems pleased, in a feline sort of way.

Reminder that being left-handed means dealing with daily little bits of bullshit like Bluetooth phone/headphones combos that have lots of interference if the phone is in your left pocket ¯_(ツ)_/¯

Yesterday’s bike ride through East Van was pretty nice!

RPG maaaaaps! (find the banana for size)

I finally got around to frame that awesome poster I got with my copy of “The Bitmap Brothers: Universe”!