I don’t like blue skies. Give me some

clouds!

The Stochastic Game

Ramblings of General Geekery

Got a few more rare Glorantha fanzines…

Good morning!

Say hello to mama! (art by… me, inspired by true events)

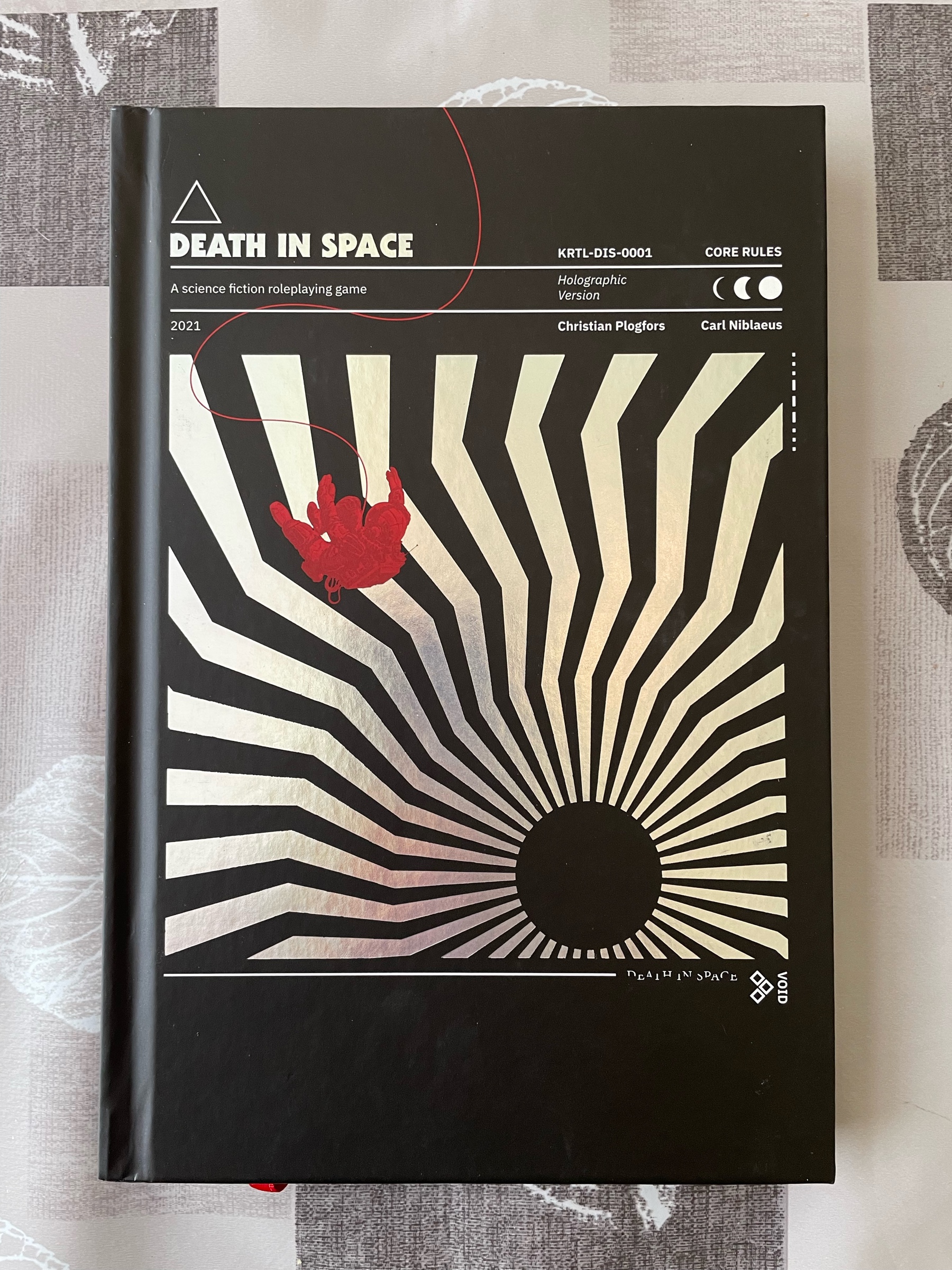

New arrival! Death In Space #ttrpg

Good morning everyone!

My kid is singing a song about how our dog is super cute, but set to the tune of the Star Wars Imperial March. I’m a bit confused.

Time to watch this again apparently. A kid requested it…

It’s a chill jazz Chrono Trigger cover sort of afternoon here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYgQEjcosP0

Canadian subway scene:

Guy1 (parking his wheelchair): hey move please

Guy2 (ignores him)

1: fucking move!

2: whatever (still ignores him)

Others: dude just move! (guy finally moves)

1: fucking immigrants

O: wtf man we are all immigrants

1: yeah sorry, my grandparents were too