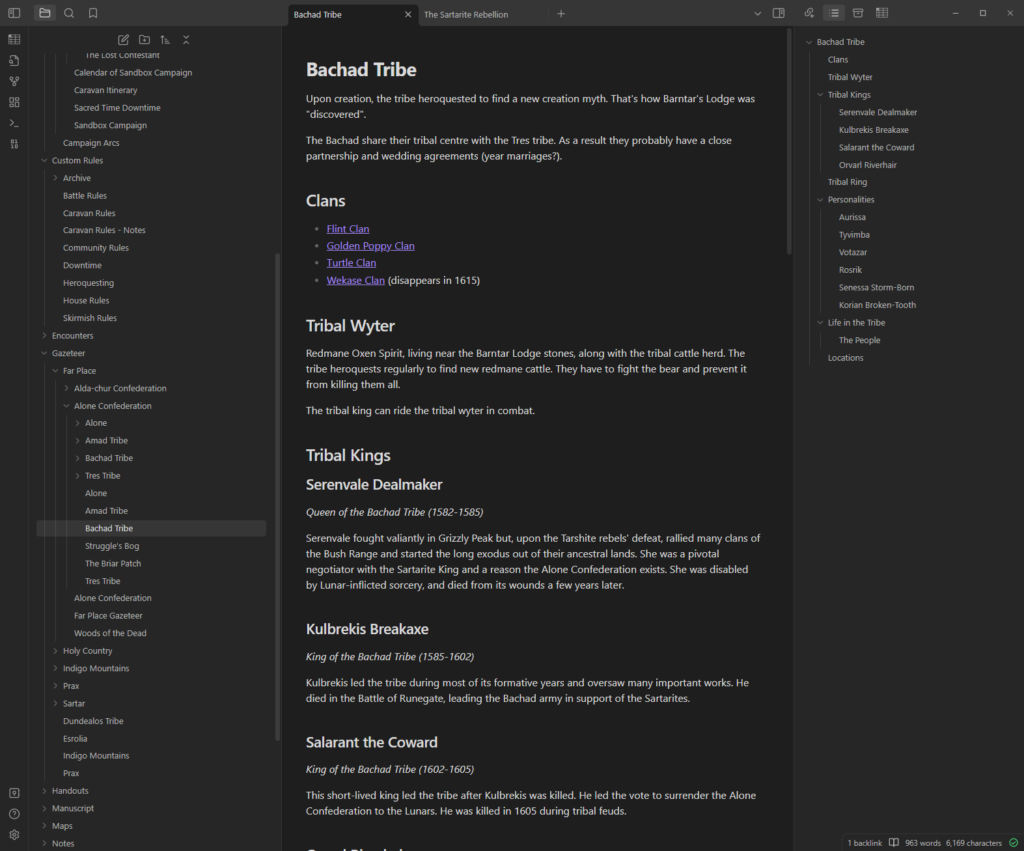

This inaugural article by Sarup Banskota for the OSS History newsletter sent me down a little nostalgic trauma trip:

Unless you’ve been writing code for decades, you’ve likely never used a VCS besides Git. However Git is far from being the first important VCS.

The World Before Git

What follows is a short history lesson about source control, from the early days of RCS to the modern day of Git. I remember being confronted to CVS in the late 1990s during an internship, and I was completely confused. I don’t think our software development professors ever taught us about source control, so the very concept of it was fairly alien to me at the time.

Later, in one of my first corporate jobs, I started using Rational ClearCase, which was anything but. That’s probably when I learned about branching, and when I got really interested in source control. At home, I got on board with Subversion (SVN) and that was the first VCS I ever truly enjoyed using. For solo projects, it just worked, kept out of your way, and early software like TortoiseSVN made it super user friendly. I was quite surprised by this bit, though:

A key idea SVN introduced was that of atomic commits. With CVS, when a commit operation failed halfway, it would lead to data getting corrupted. Part of the files would get saved, and part of them would be lost. SVN’s commits took an all or nothing approach, ensuring reliability.

The World Before Git

It’s amazing to think that atomic commits weren’t a thing before the early 2000s.

Sarup glosses over a few things about how Linus Torvalds came to write Git, though. As far as I know, it wasn’t so much about the controversy around an open-source project like Linux using a proprietary system like BitKeeper. It probably played a role, but I think the main impetus came from BitKeeper terminating their free license.

Of note, around the same time, Olivia Mackall (known back then under the name Matt Mackall, or mpm) also started working on Mercurial, with the same goal of replacing BitKeeper. However, Linus came out with Git a few days earlier, and Git was adopted over Mercurial for obvious reasons. Still, Mercurial is the only other VCS, besides SVN, that ever truly liked. It just makes sense to me, and when I use it I rarely have to scream into a pillow afterwards the way that all other VCSes make me.

I actually like Mercurial enough that I wrote a few things for it: a plugin to push/pull from multiple remote repositories (now maintained by Marcin Kasperski), a Vim plugin (ironically also available on Github), and, oh yeah, the Mercurial hosting implementation for Sourcehut, among a few other things.

Meanwhile, over here in the game development industry, Perforce reigns supreme. The main reason is that source code is a rounding error in our repositories: binary assets (3D objects, textures, audio, animation, etc.) take up dozens and dozens of gigabytes, up to a couple hundred gigabytes for big AAA games1. Add to that many branches for different releases or GDC demos and so on, plus hundreds of commits per day, and the Git/Mercurial model of cloning and merging utterly fails.

Some game developers argue about storing code in Git and binary assets “somewhere else”, but with tight dependencies between code and data, the act of keeping the two in sync becomes tricky (although I’ve seen some game studio attempt it). Other game developers argue about investing in Git LFS in the way that, say, Microsoft did to make Git work with their massive codebases. But of course nobody has that sort of money to throw at problem that isn’t their core business.

At some point, Plastic SCM looked like an interesting competitor to Perforce, but that didn’t go anywhere, and then Unity acquired them and squandered them away. Meanwhile, the Git hype is so strong that Perforce has spent years trying to chase it, instead of, you know, taking care of their customers who need something different from Git in the first place. I think there’s a great opportunity for someone out there to write a VCS that properly addresses the needs of the video game industry and be the, well, maybe not the hero we deserve, but the hero we need.