Some Notes on Numenera

Numenera is a science-fantasy game set in the far, far, far distant future, with some lightweight and somewhat original system, all written by Monte Cook.

On paper, it ticked a lot of boxes for stuff I’m interested in, so I brought it to my Friday group a few years ago. We played a dozen sessions or so and… well, we weren’t much into it and dropped it for something else. Still, there are a few cool things to take away from Numenera! Here are my notes!

Disclaimer: we played Numenera several years ago, using the game’s first edition. Since then Monte Cook published a new edition, called Numenera Discovery and Destiny. I have no idea what changed in that second edition.

The Ninth World

Behold the Science-Fantasy Crazyness

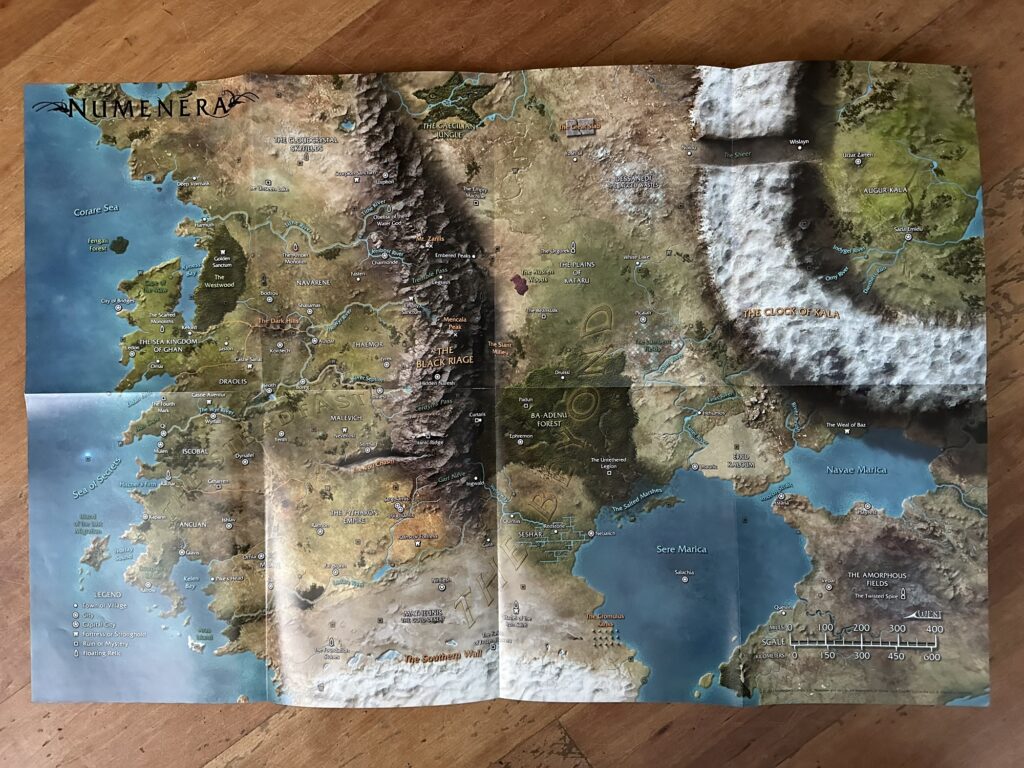

The main thing that originally drew me to Numenera was its science-fantasy setting. There aren’t many of those, and Numenera’s “Ninth World” takes the concept of “sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” to some really fun places. It cites Moebius as one of its two main inspirations, so that’s a win. And finally, it comes with a big-ass poster map, and you know I can’t resist a game with a big-ass poster map.

As soon as you look at the map, you can tell the Ninth World is a place of high science-fantasy concepts. There are big weird things thrown at your face like the Voil Chasm, the canals of Seshar, the Great Slab, the Cromulus Ranks, and the colossal continent-size Clock of Kala.

The idea is that the Ninth World is “built on the bones of the previous eight”. Each of these worlds was an age ruled by a specific “race” whose “civilizations rose to supremacy but eventually died or scattered”. This premise supposedly explains why there are a variety of ruins and artifacts all across the map, that all look and function in weird and different ways… sadly, that’s already where Numenera started to lose me.

Even if you consider Earth’s different time periods from the Stone Age to the modern day as “previous worlds”, there isn’t that much left. And that’s not just because a lot of that stuff degrades, deteriorates, or gets covered in sand or dirt in a matter of centuries — it’s because whatever remains gets transformed or destroyed to make room for new stuff. But here, we’re told that functioning gadgets and techno-temples and satellite arrays from “vast millennia” ago are still around. On Earth we may still have Bronze Age tablets and Iron Age monuments, but the former have been picked up and moved to museums to build apartment complexes or gas pipes, and the latter have been repurposed as churches or whatever in the Middle Ages. My disbelief has trouble staying suspended when I think of, I don’t know, some nano-machine civilization looking at an old floating island with a ball of energy on top and thinking, huh, let’s leave that there.

Everything and the Kitchen Sink

But sure, I can make an effort and accept the high-concept premise if that lets me play in a cool setting. The second problem, though, is that I didn’t find the resulting world-building very compelling. It ends up being a mish-mash of various crazy inconsistent ideas, brought together with the excuse that all this stuff comes from different ancient civilizations.

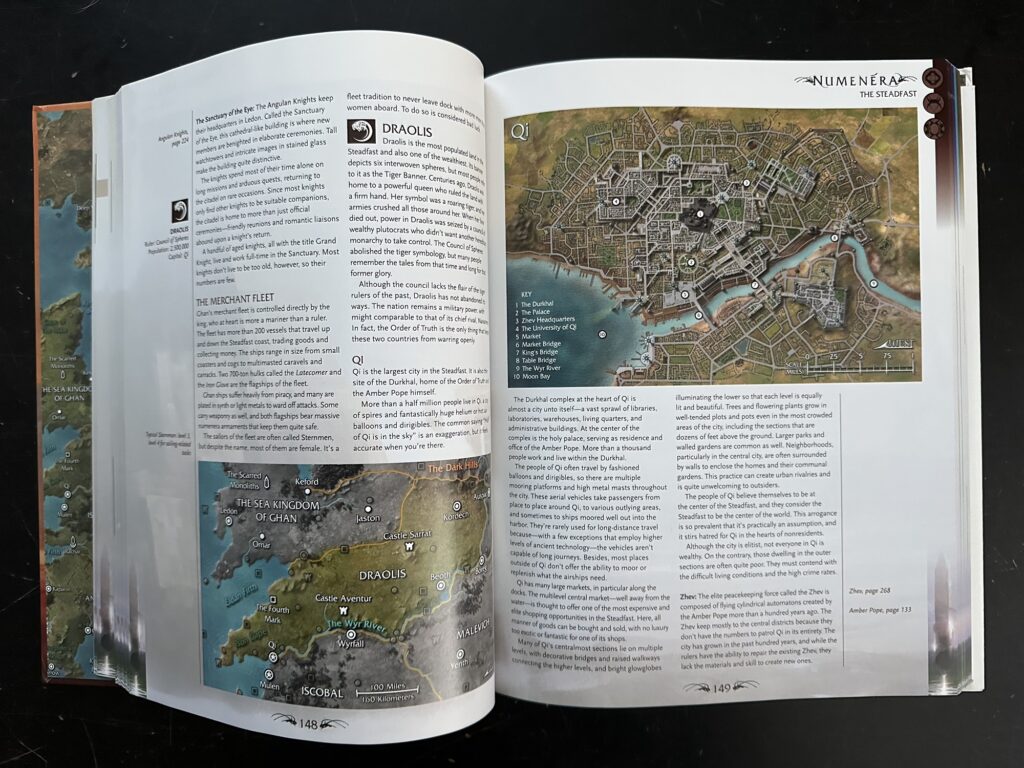

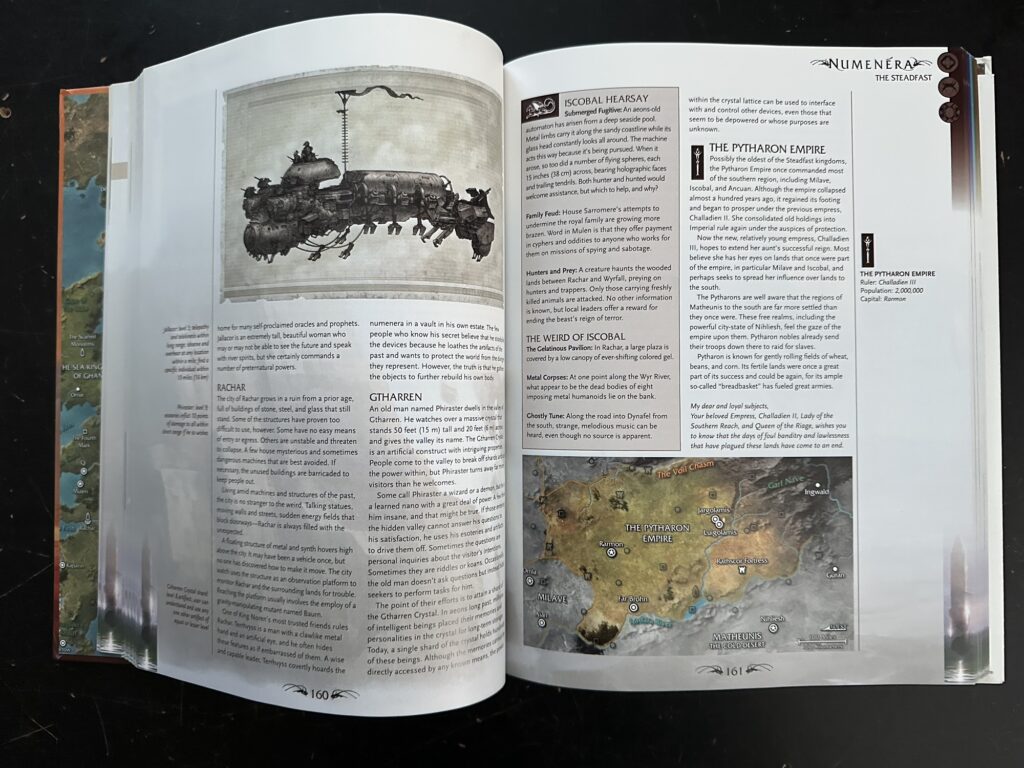

Taken in isolation, there’s a lot of cool ideas. There’s a deadly storm called the Iron Wind made up of rogue “nano-spirits” (i.e. nano-machines) that can tear you apart. There are trees with mysterious doors opening in them. There are fortresses equipped with ancient sonic shield devices that nobody knows how to recharge. There are mountains sculpted by ancient technology into impossible shapes, and there’s a city regularly visited by strange holograms showing the recent past. There’s a mesh of satellites beaming information to the ground, and there’s a big floating monolith that affects the local weather. There’s a place with a partially unexplored honeycomb of precisely carved tunnels, and there’s a village that grows plants atop the carcass of an old crashed spaceship whose engine is still humming and providing heat. There’s a city where people travel by balloons and dirigibles. And this is all rounded up with evocatively named people like the Amber Pope, the Angular Knights, the Windriders, and the Aeon Priests.

I can see how someone might read through this stuff and think that it is inventive and varied and exciting. That’s what I expected to think, but I ended up thinking it’s just too much. It’s everything and the kitchen sink. It’s a mess. I didn’t relate to it much. Maybe I might like it better if I read the book again in the future, when I’m in a different mood? After all, I bounced off of Glorantha a couple times in the past before I found it again a few years ago and fell in love… so who knows!

The Steadfast and the Beyond

Anyway, if you want to know a little bit more about the Ninth World, know that the map is basically divided in two halves.

The western half is the Steadfast, the somewhat populated and civilized part of the setting. You can think of it as some late Bronze Age setting, in terms of population, literacy, everyday life, and social structures. The main difference is that while Bronze Age cities each had their own patron god with supposed powers, the cities in Steadfast each have some old techno-magic remnant they’re built around. Some worship it, some use it as a tool, and others just live on it. But this gives each place a unique look and concept, and also generally explains why every place is so different: in most cases, that techno-magic remnant is unique, people barely know how it works, and for sure nobody knows how to replicate it or move it. In fact, half the time in Numenera, people use one of those old artefacts in completely the wrong way, or mistakenly think that some side effect of its original purpose is its main purpose, not seeing the big picture. This is one of the places where the science-fantasy of the Ninth World really shines, and why I’m a bit sad that I somehow didn’t take to it.

The eastern half is the Beyond. That’s the somewhat unexplored part of the map, where settlements are smaller and more isolated, and where the weirder shit happens. There are leftover machines hundreds of meters across, there are weird techno-towers in the middle of nowhere, there’s a star-shaped forest where mechanical predators roam, and so on.

By now, I think you get the idea: it’s full of weird stuff. But more importantly, this is the sort of setting where you have to travel around. It would be a waste to simply pick one spot on the map and run the whole campaign there, the way you might do with, say, running an entire Forgotten Realms campaign in Waterdeep.

The Cypher System

Okay let’s talk about the system, which is named after one of the cool ideas of the game that I’ll talk about a bit later.

The Good Old Polyhedral

This being Monte Cook, of course the Cypher System is a D20-based system in which you need to beat a target number. It gets a bit finicky for no reason about bonuses and the target numbers, though. First, it defines rolls with a “task difficulty”. The target number is three times the difficulty. So rolling for a difficulty 4 task means rolling against a target number of 12. Having a “trained” or “specialized” skill lowers the difficulty by one or two, which means lowering the target number by 3 or 6. Some abilities or equipment provide bonuses to the roll, but if you get a +3 bonus, the rules say to ignore it and instead lower the difficulty by one, which lowers the target number by 3… uugh. Why? I’m not allergic to crunch and math (I play GURPS!) but this seems unnecessary? I think we just ended up dropping the task difficulty terminology, only talking in terms of +/-3 modifiers.

A few other things are notable about the system. First, the GM never rolls. This was my first time GM’ing a system like that. If a player attacks a creature, they roll to attack. If the creature attacks back, the player rolls for defence. I can’t really say that I was a fan of that. I like my dice! I like rolling them! However, I will confess that it noticeably frees up some brain power to do other gamemastering things, so it has some upsides.

A second notable thing is that damage is fixed. You don’t roll for damage: you deal a fixed amount. Combined with the GM not rolling, you should see how action scenes play very fast with the Cypher System, which is good if you’re into that. I was OK with it but some of my tactically-inclined players felt it was too light.

GM Intrusion

A third interesting thing about the Cypher System is how it awards XP. This works with “GM Intrusions”, which is when the GM interrupts the game to offer a player some narrative beat. Of course, this is generally something negative for that player character (the rulebook offers the rather classic and lame “you drop your weapon” as an example). If the player accepts, they get 1 XP and pick another player to also get 1 XP. If the player refuses, they must pay 1 XP. If they don’t have XP left, they can’t refuse.

On the one hand, this is an interesting mechanic. On the other hand, I found that it often made me feel like a bad, adversarial GM. It’s one thing to play evil vengeful NPCs that want to ruin the player characters’ lives, since whatever the GM attempts to do through these NPCs is mediated by the rules. But here, the GM can bypass both the rules and the NPCs. You don’t tell a player that they drop their weapon because they rolled a fumble, you tell a player that they drop their weapon just because you feel like it. And the player can’t even do anything about it if they don’t have an XP left. That’s just not how I want to GM.

Luckily, the rules do also have “guided” GM intrusions:

- If you roll a natural 1, that’s sort of a fumble and the GM gets a free intrusion.

- All creatures in the “bestiary” chapter have a special ability described as a GM intrusion, like poison or paralyzing effects.

I ended up mostly using that, and almost never using the other type of GM intrusions. Instead, my players would occasionally offer intrusion ideas to me in exchange for XP, and that reversal of the relationship worked better for me. I’d recommend implementing that as a house rule if you also feel uncomfortable with GM intrusions as written.

Stats and Effort

Characters have three stats: Might, Speed, and Intellect. That’s short and sweet. Again, it’s a lightweight system. Each stat has two components: your Pool, which is your current score in that stat, and your Edge, which is like a modifier for doing things with that stat at reduced cost. Your Pool and Edge for each of the three stats is determined by your character class.

Now, the problem is that these stat Pools are used for two conflicting things. On the one hand, they represent your hit points. You reduce your Might pool when you get hit by a weapon, you reduce your Intellect Pool when you suffer a psychic attack, and so on. On the other hand, you can also spend points from your stat Pools to apply “effort” to a roll. Spending 3 points from a stat Pool decreases the difficulty of a task by one step (which, you might remember, decreases the target number by 3).

You should be able to see the problem here. In a few places, the rulebook tells you that exploration is the “soul of Numenera” (discovering new stuff is actually one of the only other ways to gain XP besides GM intrusions). You’re encouraged to spend effort on rolls made to climb ancient monolith structures, figure out weird alien control panels, or pry open mechanical doors who lost power millennia ago. But sooner or later, there’s going to be danger. You’ll wake up some ancient defence drone, you’ll disturb some dangerous wild animal who made its lair in the ventilation shaft, and you’ll fight off Aeon priests who want to get the McGuffin before you. You’ll need your hit points for that! So my players quickly decided to almost never spend points for effort, because it’s better to fail at something and try another way, rather than get through the door and face the ancient machine-surgeon with a half your HP. In the end, my players were less motivated to do cool stuff during the exploration phase (i.e. attempt more daring actions by spending effort), because they were saving their points for a possible later action scene.

You might remember that I also had a similar problem with Blades in the Dark, whose “Stress” points are also used for two things. I had recommended making flashbacks free to start (with the option to spend Stress inside the flashback). I have no mechanical recommendation here. Instead, I tried my best to manage player expectations, sometimes with a bit of annoying meta-gaming, to clarify whether there’s a combat scene ahead or not, or whether there’s an opportunity for resting first or not.

Characters

The rulebook only comes with three character classes: the Glaive (which is the sort-of fighter type), and Nano (which is the sort of techno-wizard type), and the Jack (which is the jack-of-all-trades). This looks fairly limited at first glance, but given there are only 3 stats in this game, it’s actually the right number.

The way you make you character feel unique is with the “character descriptor and focus”, which is reminiscent of narrative systems like FATE or HeroQuest/QuestWorld, but applied to a D&D-style ability buffet. You effectively fill up the following sentence: “I am a X Y who Zs”, which defines what your character is good at, and known for. You’ve got a bunch of choices for X, Y and Z. For instance, “I am a Tough Glaive who Rides the Lightning”. Both the descriptor (“Tough”) and the focus (“Rides the Lightning”) give you extra abilities and stat bonuses, with a level-based progression path, so those seemingly limited 3 character classes suddenly expand to a whole range of combinations. That Glaive character with electricity powers is a lot different from a “Graceful Glaive who Fuses Flesh and Steel” for instance. You can pick some great and weird character concepts in there, and the only game so far that reminded me of this sort of weirdness is Spire.

I’m pretty sure that adopting this “X Y who Zs” approach is pretty easy in most game systems, and could make character creation more fun.

Cyphers, Artifacts, and Oddities

Okay, the last thing I want to talk about is how Numenera handles all those weird techno-relics you can (and want to!) find in the world.

- Artifacts are devices with a reproducible result. They are generally moderately large, like a vehicle or a portable communication system. They’re the most useful and sought-after relics, and you get XP when you find one.

- Cyphers are small devices that only have one use. They are spent, depleted, destroyed, or whatever after you use them.

- Oddities are just plain weird stuff that nobody knows how to use, or how to stop it, or how it’s useful.

All three types of relics are offered as rewards for exploring new places, or looting a felled creature or enemy.

The heart of this loot system is the Cypher, though. You can carry Cyphers around as equipment, but each character class and tier (level) has a limit on the number of Cyphers they can carry. This is explained by the fact these old techno-relics sometimes “interfere” with each other, and unless you have a knack for that kind of thing, you want to stay on the safe side by not having too many of them on you — otherwise they could trigger each other or explode or turn you into green goo somehow. If you like random tables as much as me, you’ll be happy to know that there’s a table for “Cypher Danger” when you carry too many.

Cyphers are so commonly handed out that one of the 4 panels in the Numenera Gamemaster Screen is a random table of a hundred Cyphers. The goal of Cyphers are to be found, used, discarded, and replaced by more Cyphers found. As a GM, you want to hand them out so often that your players will start regretting not using one earlier because now they have to choose which one to pick and and which one to discard. It’s a great feeling to see your players being conflicted about having too much loot!

This concept of Cyphers is one that I’ve been thinking about lately, for bringing to other games. You could hand out similar one-use items in any fantasy setting easily! That enchantment in your new shield protects from one critical success and then goes away. That enchanted compass lets you find one place of your choosing and turns to dust. That frog is inhabited by a spirit bound to answer one question, after which it can leave and go back to the Spirit World. You can also adapt the same concept to a sci-fi setting. That military hacking device was left unlocked and you can use it once before it locks again with an unbeatable encryption scheme. That pill gives you extra intelligence for 24 hours, but you only found one. That prototype gun with auto-aiming bullets only has one bullet left in it. Sounds fun to me, especially since I tend to vastly miscalculate the power of whatever loot I give my players. With one-use loot, I only have to worry about it once!

Well, that’s it for my opinion of Numenera!

Writing these notes makes me sad again that we didn’t care much about Numenera. As I said at the beginning, it’s one of those games I really thought I would love at first glance. I’m also surprised these notes ran this long! Who knew I’d have so much to say about a game I played six or seven years ago?

I hope these notes will help if you’re planning to run Numenera! Go and have fun!