Some Notes on Blades in the Dark

Last year my Friday-evening group played a short campaign of Blades in the Dark (BitD), so I figured I’d share some notes about it — mostly the bits that we did wrong or that I didn’t like, with some actionable recommendations that will hopefully improve your experience should you play BitD yourself.

We played weekly for about six months, going through many adventures. For once in a long while, I was actually simply a player, instead of being the gamemaster! I had wanted to play BitD for a while, and when one of the players said he had the rulebook, I jumped on the occasion to make him run it. So unlike many other TTRPG posts here, this one is exceptionally from my perspective as a player.

Overall the campaign was quite good. Our gamemaster portrayed a few memorable NPCs, and we got into a lot of fun trouble. My main problem with the game was a slightly-too-crunchy system, and our messing up character progression. I doubt that we’ll get back to BitD, not necessarily because we didn’t like it, but mostly because we’ve got so many other games to play and so little time.

The Setting

The setting was actually one of the two main reasons I wanted to play BitD (the other one being doing heists!) I like urban fantasy, and especially dark urban fantasy. There’s not a lot of that kind of stuff in games, unless you roll your own or tweak some existing setting into it (which I definitely did in my youth).

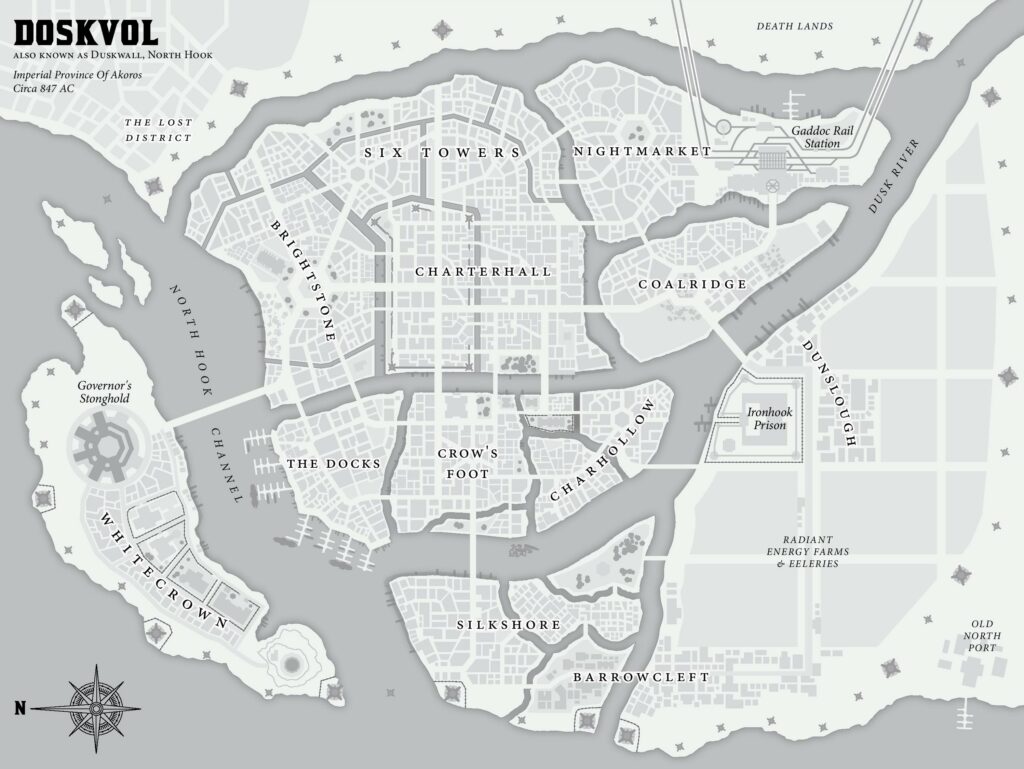

The world of the Shattered Isles is great, it’s really good world-building, but a lot of it can be skipped by the gamemaster. We stayed in the city of Doskvol all the time, of course. Most of the campaign was in the neighbourhood of Crow’s Foot, except for one (rather stressful) trip to the Lost District, and one episode at the rail station. But step two of character creation (“Choose a heritage”) introduces a bunch of other cities, islands, and cultures a character can be originally from. The information on the wider world beyond Doskvol is (intentionally) short, but I still recommend that the gamemaster heavily hand-waves it away even more.

If a player wants to play a foreigner from some exotic place, who cares that it might be called “Iruvia” and look like “old Persia, Egypt, or India”? This isn’t a game in which you’ll ever go there anyway, so simply divide characters between those who were born in Doskvol and those who were not. The latter can make stuff up. The gamemaster can give them one of the rulebook’s locales if they really don’t come up with any ideas. This will save a bit of time during character creation, when some world-building-loving players (like myself) start asking too many questions about lore that won’t matter.

The Mechanics

Subsystem Crunch

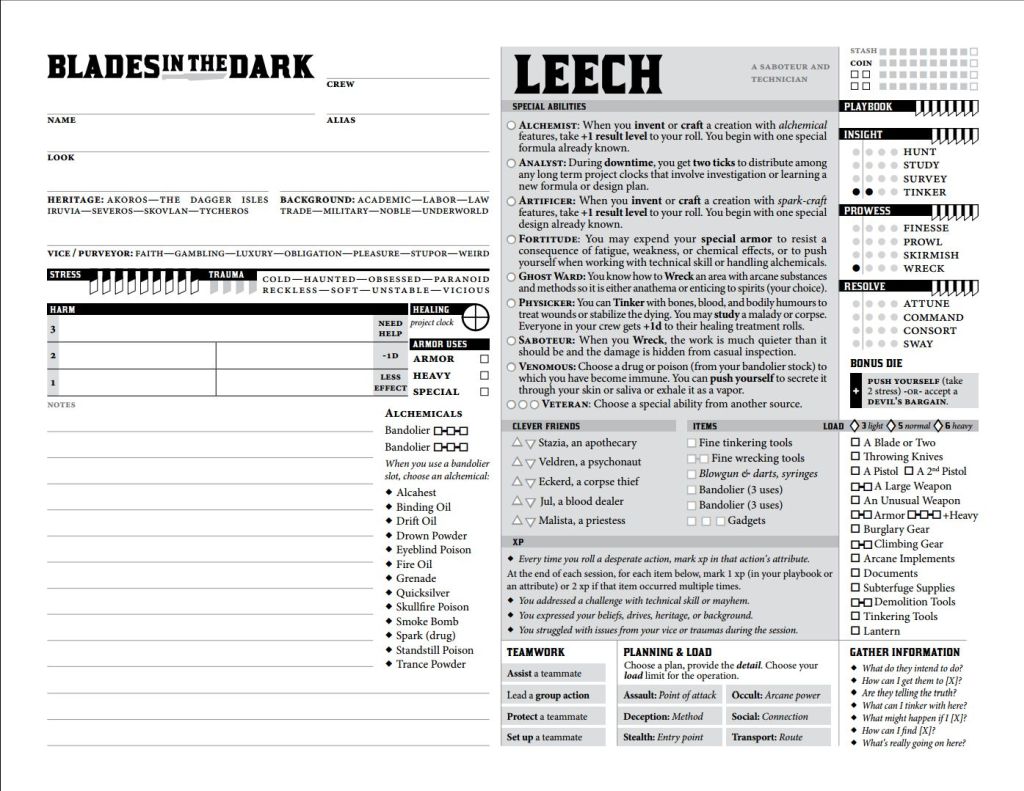

I was surprised by how crunchy BitD’s system is: it’s not just a PbtA system, it’s PbtA with a bunch of sub-systems layered on top: stress and trauma, loadouts, vices, progress clocks, harm, conditions, heat, entanglements, and so on. When I skimmed the rulebook, it originally seemed pretty straightforward. There isn’t much more to it than your average TTRPG… but the difference is that each one of these things is a different sub-system. It’s not as if all these concepts were modelled with similar stats and numbers and mechanics. Nope, they’re all different things. Loadouts are a check list with limitations, harm is a semi-free-form scale of penalties, stress and trauma are related point pools, armor is checkmarks to be triggered, healing is a progress clock to be tracked, etc. None of this uses the core mechanic of attribute, skill, and dice pool… so all of it needs to be learned on its own, with the mental overhead that comes with it.

Now of course, this isn’t Rolemaster. It’s OK, but I wasn’t expecting this, and I can’t say I like it. Some people seem to love this interlocking of various-sized gears and levers, like a finely-tuned mechanical clock. I see it more like a game designer who had a lot of great ideas, but decided to put them all in the same game. I prefer unified systems, and this clearly isn’t it.

I strongly recommend gamemasters to provide cheat sheets to their players. Thankfully, the BitD community is great, and there are many good cheat sheets out there. The official website has some, the Alexandrian has one, and there’s more to be found if you hunt around.

Core Mechanic

The core mechanic isn’t that simple either: it’s not just about adding attribute and skill to roll a dice pool. That would have been perfect… but no, the system asks the gamemaster to set a “position” and “effect”. When using Roll20’s BitD system integration, you’ll have to pick those two things on every roll, which quickly becomes tedious because it’s done in a modal way (instead of as optional settings). Maybe with face-to-face gaming there would have been lesser friction on that, but I came to see position and effect as utterly useless, especially because they have absolutely no mechanical component.

Position is supposed to model how risky the character’s action is (on a scale of “controlled” to “risky” to “desperate”). Effect is supposed to model how much this particular character’s action will affect the world and the story (on a scale of “limited” to “standard” to “great”). Only of course they don’t “model” anything: it seems to be more of a process that helps the gamemaster explain to the players what the stakes of the roll are. This process of setting position and effect lets the players know that there might be dire consequences, or that even a complete success will only give a limited opportunity to the character… this is an interesting process that might clarify things for unexperienced players and strangers coming together at a convention. In practice, I found that it slowed things down for a group of friends who know each other. We generally understand what’s at stake when we roll dice, but this whole position and effect business added confusion and more questions.

My recommendation here is to completely ignore position and effect in Roll20, clicking through the dialogs to get to the rolling. The gamemaster can verbally specify position and effect if they think that might help, but chances are that your group already has their own way of announcing what the roll will be good for. If that’s the case, ignore position and effect completely.

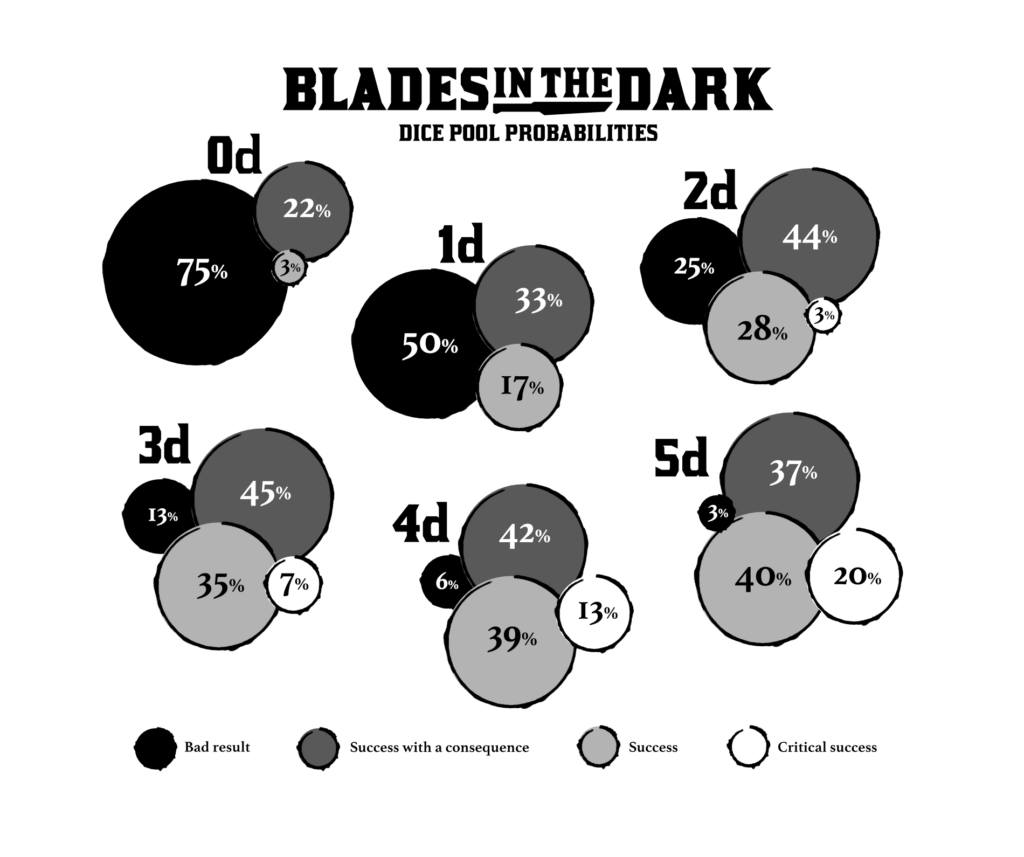

Devil’s Bargain

The other thing that kept slowing down the game was the Devil’s Bargain. This is something you can take to get a bonus die in exchange for some bad side-effect following from your actions (regardless of the outcome of the roll!) But it takes some thinking to come up with a good Devil’s Bargain that’s relevant to the action about to be undertaken. So what would often happen in our game is that we have some good action going, something is about to happen, a roll is going to be made… and the player asks “what’s the Devil’s Bargain on this?” Then the game stop for two minutes while everybody racks their brain for something more original than “someone gets hurt” or “an NPC notices you/gets mad at you”, which we probably used the last three times.

I recommend making up some table rules around Devil’s Bargain. For instance: never ask for it, but suggest something for it. That is: don’t make someone else do the work of coming up with a Devil’s Bargain. Come up with it yourself, or roll without it. This might prevent the game from stopping because the Devil’s Bargain doesn’t come up unless someone has already thought of one.

Stressful Heists

The whole premise of BitD’s gameplay is to take on heists “just like in the movies”. That is: you don’t play through the heist’s planning phase, you just start in-media-res and use flashbacks as necessary to explain how you conveniently had all options covered… but the mechanics got in the way. The same thing happened with Numenara, actually, and in both cases the problem was the dual-use of a game stat.

See, it can cost you points of stress to trigger a flashback. Once you’ve taken 9 points of stress, you get some trauma, and that’s bad. But the problem is that stress is also used for many other things: you gain stress by helping a teammate (to give them a bonus die), by pushing yourself (to get a bonus die yourself), by resisting damage or other negative consequences (most likely taking one of two stress in the process at least), from using some special abilities, and more. On the other hand, stress is hard to get back: you can recover some of it during downtime, but that’s either partial or dangerous…

We pretty much always started a heist with left-over stress from the previous adventure, and only had at best a handful of stress points to spend. Because we needed these stress points for, well, everything I outlined above, we tried to cut corners as much as we could… which included either not doing any flashbacks except strictly required, or rejecting the gameplay’s premise and trying to play through as much planning “in the present” as we could before starting the heist (despite our gamemaster’s best efforts).

My recommendation is to make all flashbacks free, but let players spend stress inside the flashback. For instance, if they want to have hidden some Bluecoat uniforms and weapons behind a bathroom tile, let them attempt it for free (by RAW it should have cost 1 stress)… but let them use stress points as usual: for helping each other, for pushing themselves, or for resisting the consequences of, say, being caught replacing the tile. If the players want to save on stress, they can still enjoy playing through the flashback but they come out of it with increased Heat or stained uniforms or whatever. The goal is to encourage players to do flashbacks, not hoard stress. The nice advantage of this house rule is that it also removes another burden from the gamemaster, who won’t have to figure out if a flashback idea should cost 0, 1, or 2 stress points.

Characters

I’m not a big fan of class-based systems in general, and of Powered-by-the-Apocalypse (PbtA) systems in particular, but as a player I don’t mind it too much (it’s a different proposition as a gamemaster). The BitD playbooks are all pretty straightforward, with interesting narrative abilities. But my main problem was character improvement, or lack thereof.

There are multiple experience tracks in BitD. There are XP tracks on each of the three skill groups (Insight, Prowess, Resolve). When you get five XP checks in one group, you get a new point in one of those skills. Getting an XP check requires attempting a “desperate” action, i.e. a dice roll with the “desperate” position (see “Core Mechanic” above) Needless to say, this didn’t happen very often. First, this XP mechanic is entirely dependent on the gamemaster’s whim at a particular moment. Second, it was very common to go several weeks without getting any XP check in our skills because we were understandably trying to avoid desperate situations to begin with. That’s what doing heists is about: getting in and out before trouble finds you. And sure, the exciting bit is when trouble does find you, but I find that the game design is wrong, here, as it seemingly encourages players to both try to avoid trouble (for narrative reasons) and try to get into it (to get XP checks). In particular, the player advice chapter has a section called “Go Into Danger, Fall In Love With Trouble“, which encourages you to do risky stuff. In my experience, it might give you a few XP checks, but it also leads to unsustainable complications and entanglements after a while.

The other XP track is the “playbook advancement” track, which lets you buy new special abilities from your playbook. You need 8 checks to get there. To get one check you need to have “expressed your beliefs, drives, heritage, or background”, “struggled with issues from your vice or traumas”, or addressed a challenge according to your playbook’s “style”. The first two are rewards for roleplaying, effectively. The last one is a reward for acting the way your class is supposed to act. My first character was a Whisper (“arcane adept and channeller”) so I was supposed to solve problems using magical knowledge and power. My second character was a Spider (“devious mastermind”), so I was supposed to solve problems using scheming and plotting. The problem here was pretty much entirely our fault. We’re old experienced gamers, and we’ve seen many systems… so when a system says “get an XP when you roleplay” we tend to interpret it as “get an XP when you do some particularly cool roleplay” (which is what you tend to find in other systems). That was obviously a mistake, because we only got at best a handful of XP checks for each character.

Of course, it gets difficult to improve a character when you switch between two characters, spreading the XP you obtain. That was a consequence of the stress problems I outlined previously, which led us to basically refuse doing flashbacks during heists. Our stress was going away so fast that we needed to spend several downtime rounds “indulging in our vices”, which is how you can recover stress in BitD. But that comes with some risk of over-indulgence, which brings trouble to your crew or forces you to “retire” your character for a session or two. All of this happened, and the heat we would bring to the crew would get worse so we eventually all had to create an alternate character in order to let the first one rest and recover their stress. When I hear people describe BitD as a “finely tuned clockwork of a game”, my experience is rather a “horrible death spiral of stress and complications” once you’ve played more than a dozen sessions.

As far as I remember, none of our characters ever gained a second special ability. Some of us got a couple of extra skill points but that’s it. After six months of weekly play.

The first obvious fix is to not be over-achieving grognards who don’t correctly read the rules. This means that XP checks should show up on a regular basis on the playbook advancement track. Any self-respecting roleplayer would have, of course, brought up some aspect of their background into play in any given session, even if it was a simple beat in an NPC interaction, or some choice opinion during a debate back at the Hideout. It shouldn’t take a full-blown roleplaying scene to earn those XPs, and that was our mistake.

The other fix is trickier, and I don’t have any good ideas. Getting the gamemaster to declare a roll as “desperate” when it doesn’t actually have any mechanical consequence will vastly depend on your gamemaster. At this point, I’m frankly tempted to recommend throwing the entire XP system away and replacing it with a much more straightforward and automatic process that won’t require players begging the gamemaster (I really dislike it when games do this). Something like: one XP per session, plus an extra XP for completing a heist or tying up a narrative thread, like a character goal. Each XP point must be immediately allocated to a track (ability track or playbook advancement). Boom, done. Maybe new players need a carrot to do a bit of roleplay and attempt daring feats, but chances are you’re experienced gamers and you don’t need that anymore.

Campaign Play Takeaways

Overall, BitD has a lot of very interesting sub-systems, but it was a bit too much for me. More importantly, these systems might work only if you play the game in the specific way it wants to be played. The rulebook has a very good section on both player guidelines and gamemaster advice, and it shouldn’t be ignored. I made the mistake of only skimming through the player section before we started the campaign, and I wish I had more closely read it instead. None of the other players had the book. I strongly recommend that a BitD gamemaster prints out the player guidelines chapter and hands it out to all the players during Session Zero.

The other big takeaway is that the gamemaster can’t completely trust the system to generate the skeleton of the campaign storyline. After several months of play we had many complications and entanglements, replacement characters that were themselves becoming too stressed, a crew that accumulated heat faster than it accumulated any coin or improvements to manage that heat, and many angry NPCs. We ended the campaign before it became unsustainable, but I can totally see that we would have reached that point after another couple months of play. I would strongly recommend that a BitD gamemaster keep an eye on the number of story threads and complications. Just stop following the downtime rules once you’ve reached a good narrative spot, and drive the storyline “by hand” from there. Once some of those threads are tied up, start following the rules again to see what else happens. You could alternatively follow the rules all the time but heavily tweak or massage the results along the way to keep the storyline from diverging into too many complications.

That’s it for my thoughts on Blades in the Dark. Hopefully it will come in handy if you’re planning a game! My next game notes should be on Mutant Year Zero.